|

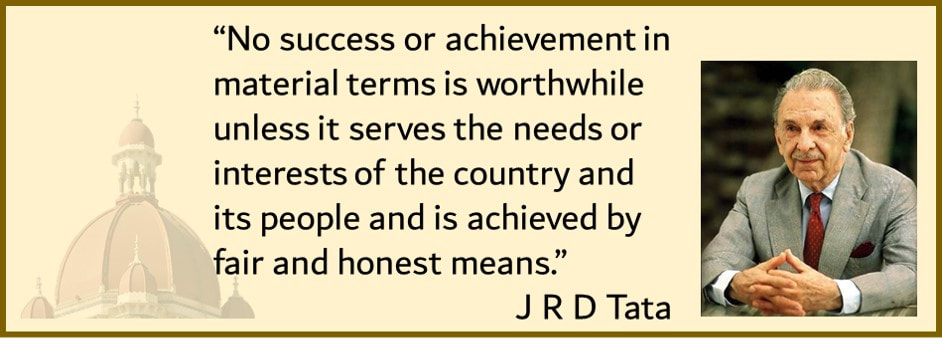

Let’s go back two decades to one of the Taj properties in Kerala. One Sunday morning, a food inspector arrived at the hotel and approached the deputy general manager (DGM) with his intention to inspect the premises. He was promptly invited into the kitchens for his checks. However, he was hesitant. Instead, he said, “If you insist I’ll check. But I am a reasonable person and don’t like to create trouble.” The DGM knew where he was heading and so he said, “You’re most welcome to join us for lunch.” The inspector declined the offer saying he didn’t have time and had to leave at the earliest. After a lot of back and forth he said, “You give me ₹6,000 and I’ll leave.” The DGM flatly refused. He said, “I will not, I cannot.” The inspector threatened him with serious repercussions and said that he could put the hotel in trouble. Concerned with his attitude, the DGM shared the matter with the GM. But the answer remained the same—the inspector was welcome to do whatever assessment he wanted and satisfy himself. Low on fatFinally, he entered the kitchen and went straight to the yogurt section to check the quality. The chef was very happy, because the practice at the Taj was that after buying milk, milk powder was added to it to ensure that the curd set very well. So there was no question of any problem. Yet, surprisingly, the inspector’s report indicated that the fat percentage in the curd was lower by 2.4 per cent. Now the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954, is a non-bailable offence. A GM could go to jail if his hotel was found guilty, and nobody except the chief minister of the state had the authority to save him. So the inspector slapped those charges against the Taj hotel. With a villainous smile he said, “All I was asking for was ₹6,000. I told you, I’m a reasonable man. But you didn’t want to listen.” Over to the courtsNow the hotel had to approach lawyers to defend the case. In those days, a lawyer charged ₹10,000 as appearance fees. On the first appearance, the inspector intentionally didn’t turn up at the court. The second time he came without his file and apologized. The third time he came, but made some other excuse. Now, this had cost the hotel over ₹30,000 simply in legal charges. Finally, the GM decided to go and personally meet the chief minister of Kerala in Thiruvananthapuram. In those days, the Taj did not have a property in Thiruvananthapuram. And so the GM and DGM had to stay in another hotel for two days. That amounted to ₹8,000 per day plus meals and travel costs. Finally, when the GM met the chief minister, he was surprised at a case filed against the Taj. “What is this case? How can there be a food adulteration case against the Taj! I myself eat at the Taj hotels,” he said. Realizing the ridiculousness of the case, he instantly squashed the inspector’s order. The real outputAfter that day, that inspector never came back to any of the Taj hotels in Kerala, because he knew it was a waste of his time. He knew that every time he would come and level wrong charges against the Taj, he would get called to the court, and his “earning time” would get wasted in legal hassles. Thereafter, he would always tell his peers, “Tata ka hotel hai—chhodo.” (It’s Tata hotel, leave it.) A permanent behavioural change was made possible. That was the real output of the ₹50,000 investment by the Tatas.

0 Comments

|

Vijayakumar Kotteri

Abstracts from works of different authors. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed