|

Why does humor in the workplace sometimes have magical effects and at other times is disastrous? The answer is not as simple as “some jokes are better than others,” or “some people are funny while others are not.” The reality is that injecting light-hearted remarks into professional interactions always entails risk. Our interest in humor in health care emerged unexpectedly during explorations of a large dataset of patient comments aimed at understanding what patients value most in their care. Artificial intelligence and natural language processing were used to extract positive and negative insights from comments in 988,161 survey responses received from patients about their experiences across the United States during 2020. Of these, 17% were inpatient and 83% outpatient experiences, respectively, and it is possible that some of the responses were from the same patients. From these comments, our analytical technology extracted 1,270,000 insights and categorized both positive and negative insights into themes and subthemes. This technology makes it possible to identify issues that are important to patients but may not be captured by standard survey questions. In fact, there are no survey questions to our knowledge in which patients are asked if they found their doctors or nurses humorous. But in our analyses of patients’ narrative comments, humor came up repeatedly when they described positive experiences with their clinicians. Patients commented on how their clinicians interacted with them, and regardless of what survey questions they were asked, they seemed to see the clinician’s ability to use humor in difficult moments as reinforcing acts of caring. A valued condimentOur analyses indicate that humor is not the main course when it comes to caring but is more akin to a valued condiment. The actual main course that is appreciated by patients is courtesy, respect, and related subthemes. Patients don’t remark on the technical skill of clinicians very often, but their comments suggest deep appreciation of empathy, kindness, helpfulness, and patience. And when patients note that care with these attributes was accompanied by humor, the humor seems more than welcome. On the other hand, when patients perceive the absence of courtesy and respect, the use of humor by caregivers adds insult to injury. In short, humor is not a stand-alone asset or liability. It serves to amplify the positive or the negative signals that patients pick up from their doctors and nurses. This verbatim comment is an example of how humor can convey helpfulness: “I had an excellent anesthesiologist who came and explained the procedure, made me laugh, and put me at ease.” And here is one that shows lack of helpfulness: “My mother drove 1.5 hours to [town] only for [Dr. Q] to question why she was in the rehab hospital for so long, who were her doctors and ‘what do you want from me?’ My mother wanted to get up and leave. He even made a comment, ‘Well I see your CAT scan. Looks like you still have a brain. I see you still have a crack on the skull. Maybe that’s why you still have headaches.’ My mother returned home without any clarity to the cause of her headaches let alone relief.” (More examples available here.) Although our data come from health care, we think that this basic approach is likely to be generalizable to other settings. Humor offered for no purpose other than providing a distraction is often irritating. Humor in the absence of obvious courtesy and respect can be taken as callous disregard. Adapted from When Is Humor Helpful? published in Harvard Business Review. Image: https://bit.ly/2ZDKvGR

0 Comments

Remote work in some permutation is here to stay. But the home-work environment continues to be muddled with challenges. It presents extended periods of labor in what are often confined spaces, a tight integration of overlapping personal and professional time, and limited physical social interactions with colleagues. In a survey in the U.K., more than 80% of the respondents said they experienced changes to their perception of time during the coronavirus pandemic. The absence of a clear transition from weekdays at the office to weekends at home has been disorienting. In our research on the business of space, teleworking, and the relationship between technology and isolation — and conversations with 10 middle management teams at technology companies, including Google, Oracle, Xilinx, Microsoft, Salesforce, Indeed, and Facebook — we have identified a model for how to manage a typical hybrid work environment: the organization of work during space missions. There are surprisingly helpful cues managers can take from how astronauts structure their time and their routines that lead to better planning and execution of work in a compact environment. The power of routineRoutines have great value. Defined by Martha Feldman and Brian Pentland as “repetitive, recognizable patterns of interdependent actions carried out by multiple actors,” routines enable organizational work to stay on track through habit-forming behaviors. Their institutionalization over time creates prompts that trigger specified responses. During a crisis, routines undergo changes and evolve. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us have found ourselves working from home in our pajamas, having breakfast while logging on to Zoom meetings, and working beyond official work hours. These routines are neither healthy nor sustainable. Meeting the inherent challenges of hybrid work, where colleagues must collaborate from different locations and are often in their personal living spaces, requires the development of new routines that support these environments. We draw on lessons from the typical space mission, which is representative of a physically disconnected work structure between the mission control — aka the office headquarters — and far-flung, task-oriented teams. Here are three routines to borrow from space missions. 1. Manufacture zeitgebers to build new rhythmsZeitgebers are external environmental cues that humans use to regulate their internal biological rhythms. They include sunlight, darkness, and changes in temperature, as well as exercising, eating, and engaging in social interactions. Astronauts have hectic work schedules that keep them very busy, they have to adjust to alterations to their natural zeitgebers — restricted physical social interactions, work rhythms that include intense activity spurts, changes in eating patterns, and a reduction in the range of emotions they feel on a daily basis. They also see multiple sunrises and sunsets a day — as many as 16 sunrises every 24 hours on the International Space Station as it orbits Earth. To deal with these disrupted zeitgebers, astronauts on space missions mark the passage of time by dining together, participating in group recreational activities, celebrating holidays, and interacting with their families via audio or video. Mission managers structure long-duration expeditions with intermediate goals, celebrating each milestone in ways that highlight the progress being made toward the overall mission goal. Contractbook, a Danish contract management platform, has introduced a variety of zeitgebers for its virtual workforce, including biweekly town halls, watercooler calls, selfie days, and a virtual gong to celebrate deal closures. (Oracle also uses a virtual gong over Slack every time a new sale closes.) Routines such as these allow staff members to celebrate small wins and replicate casual interactions with colleagues — even those they’ve never met in person. 2. Plan for both structure and flexibilityRemote working has resulted in a complete disruption of the open office concept. Instead of having an agile environment with active physical and social interaction and plentiful open space, the remote environment is exemplified by extended periods of rigidity, both in a physical sense and a social sense. Astronauts respond to this condition by observing a set schedule and routines on weekdays, with greater flexibility on weekends. Time is also set aside for performing housekeeping duties. The goal is to create organization and consistency within the confines of a rigid environment. Xilinx adopted a new policy during COVID-19 of giving people the third Friday of the month off, specifically “to decompress employees from work-related stresses and to create a healthy boundary between work and our whole selves.” This policy introduces a new type of zeitgeber intended to reset work cycles. 3. Prioritize internal communicationExtended physical disconnection can create challenges for communication, resulting in work pressures that are differently and individually experienced by personnel. On space missions, distantly located personnel have felt abandoned and ignored and perceived a lack of empathy on the part of Mission Control in terms of comprehending the constraints and stressors of working remotely. NASA learned from these incidents and built schedules that factor in regular communication and check-ins across teams while still allowing for flexibility in engagement and interaction. Managers must understand that person-to-person communication cues — both verbal and physical — are critical. They help employees create networks and bonds within the office, inculcate organizational values, and convey systems and workflows. Salesforce has made concerted efforts to make collaboration and culture-building top priorities during the pandemic. A purposeful process for remote onboarding emphasizes building trust and strengthening relationships, using a variety of fun social activities. Organizations can succeed when employees who are based in the terrestrial capsules they call home have the benefits of structure and frequent communication with their peers and managers. Adapted from What Space Missions Can Teach Us About Remote Work written by Tanusree Jain and Louis Brennan and published in MITSloan Management Review on November 16, 2021.

Images: https://www.enjpg.com/img/2020/outer-space-6-e1608499595386.jpg http://www.clipartbest.com/clipart-RidKRnpi9 Sit with your heart for a few moments, Just quiet mind chatter briefly and let silence be. You may find something rather amazing Beneath everyday anxiety and worries and busy-ness. You may find a pool, A deep spring of gratitude – Of gratefulness in the acceptance Of all the opportunities Everything that happens to each of us Offers us. Ah, but you may also find This pool is only accessible In this moment, in this day. One can drink from it Only out of cupped hands. Can you bring buckets? Huge containers? Can you hoard this life-sustaining water? Store it up against shortages in the future, Future droughts? Not in my experience. You might find you can only come to this pool When you need it And drink from cupped hands Enough to quench your current thirst, Supply your current needs. Trust This pool is not prone to drought – Unless Mind forgets gratitude Holds onto thoughts of entitlement Becomes resentful Judges all around by measures of expectations Shedding ‘shoulds’ on all it sees and hears Poisoning the pool. Now what to do? Try letting mind open once again to trust, To acceptance, Rooting out resentments Refusing to entertain thoughts of entitlement Jettisoning judgements Emptying itself of expectations. Approach the pool again, Watch the waters clear Cup your hands And stoop once more to drink And taste the sweetness of the purity of gratitude, Its graciousness. Drink deep And be sustained through all times Even times of terrible darkness And sometimes seeming overwhelming challenge. It seems the waters of Heart’s pool, The spring of hope and healing, Always renews itself If we but give it the chance – And remember to trust, To accept, To appreciate. Poem by Lorraine Brown

Our culture falsely conflates who we are with what we do for income. Thus, we judge someone’s interests, values, and how meaningful their life is based on their job. Drawing these conclusions on someone’s identity and worth is never more prominent than when someone is unemployed. The silent determination, whether we admit it or not, is that if someone does nothing, they are nothing. Identity fulfilmentAccording to Esther Perel, “we see our jobs as a place for identity fulfilment”. Perel explains that if we go back just three generations, work looked very different. We were likely to live and work in the towns where we grew up, often in the same roles as our parents. We didn’t partake in $100,000 degrees or spend hours perfecting resumes, cover letters, LinkedIn profiles, and twitter bios to ensure that our work aligned with our lives’ goals, values, and purpose as we do now. In the past, our work was more conspicuous: if you worked in the bakery, people would see you there and know whether you made good bread; if you were a builder your house might demonstrate your work ethic in practice; if you were a teacher, the whole town might know how you taught and whether the kids in your class were better educated than the other teachers’ kids. By comparison, our work today is incredibly hidden and complex: only 25% of people can accurately describe what even their spouse does at work. Yet, our titles and employers should sufficiently convey who we are to total strangers. How have we got to this? This false concept of work as expressing identity and thus meaning was perpetuated to benefit your employer, not you. Capitalist color?Most famously, Deci and Ryan codified and popularized these ideas in their publication Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour. At its core, the theory states that, to make people behave in a certain way for a sustained period, the individual must believe that the behaviours are aligned with, and reinforcing of, the individual’s sense of self. In other words, if someone is going to do something on an ongoing basis (e.g. ride a skateboard) that person must believe that that behaviour reflects who they are as a person (e.g. riding a skateboard is rebellious and cool so I too am rebellious and cool). Therefore, if you want a population en masse to produce, distribute, and exchange wealth for the entirety of their lives, you need people to view these behaviours as both demonstrating and reinforcing their identities. The addition of purpose fulfilment through work furthers and reinforces this notion. If we were to define the most critical aspects of our identities, we would likely do so through the language of life’s purpose. In the past, we fulfilled our purpose primarily through religious affiliation, family, and community integration. Despite these well-documented sources of purpose, engagement in each has dwindled drastically for our generation. In the UK, 52% of the public say they do not belong to any religion, and young people are delaying having children by five years on average. With these traditional pillars of purpose absent in our lives, organizational psychologists recognized the opportunity for H.R. managers to better attract and retain talent by presenting their companies as places for purpose fulfilment. You can see this put into practice on the career pages of many employers. As researcher Richard Boyatzis and colleagues found, rather than enabling individuals to achieve their vision of their ideal selves, employees work towards an “ought self”, or what they think they should be, based on their employer’s vision. Although an employee may be content in the short term working towards their employer’s goals, this can only be sustained until “one realizes that their personal dreams are being compromised because this ‘ought self’ does not match their ideal self”. Ultimately this “awakening leads to feelings of betrayal and frustration for having wasted energy pursuing the dreams and expectations of others”. Three core human needsHaving spoken with over a hundred individuals across the world about their Purpose Projects, I identified three core human needs which we expect our jobs to fulfil. Yet they do not, or at least only partially. They are the needs to:

Our core human need to strive can be described as the emotional and spiritual need for the work that we do to contribute, meaningfully, to a better world. We want to believe that our contribution to the world has left it better off, in some small way. Our jobs fail miserably at providing this. Our need to thrive is the intellectual need to learn, satisfy curiosity, and grow. To grow, we need to be challenged. Ask yourself, does your job push you to grow daily? If the answer is no, you’re not growing as much as you could be. You’re missing a core human need. Gabriel Victora, an immunologist at the Rockefeller University in New York City, built a career in music before turning to science. Science offered greater room for creativity, but music still informs his approach to research. I never thought of being anything other than a musician when I was growing up. I moved to the United States from Brazil at the age of 17 and studied classical piano for 6 years at the Mannes School of Music in New York City. When I moved back to my hometown of Pelotas in 2000, I was basically just practising for concerts: I’d practise a certain programme, then book four or five concerts and play them over a period of a month or two. It takes a lot of effort to perfect a programme, and you don’t want to play it only once. There were months where I didn’t do anything other than practise for the next cluster of concerts, and I would spend almost every waking hour practising at home. At some point, that endless practising started to take a toll. I became a bit burnt out with the whole business of performing as a professional musician. It wasn’t as creative as I wanted it to be. Enter science My father, Cesar Victora, is an epidemiologist who did pioneering work on how exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life reduces infant mortality. I thought it might be interesting to follow in his footsteps in science. My father suggested that I look up a medical-school friend of his who had a laboratory at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, and that I go and volunteer there, washing the glassware or doing whatever they’d let me do. They put me to work doing polymerase chain reactions, in which an enzyme is used to amplify pieces of DNA. I went in early in the morning, pipetted all day long, ran the samples on the gel at the end of the day and gave back some numbers. That’s the reason I’m an immunologist. If this friend of my father’s had been studying something else, I would have been something else. Music in science, science in musicWhen you’re sure of what you’re doing, as I was in music, it’s difficult to venture into something completely unknown. I remember at one point being lost in the woods with the complexity of immunology: there are so many loops of cells that tell other cells to do things that, in turn, tell the other cells to do things, and so on. Even as a musician, I was very attracted to music theory and Schenkerian analysis, (a scientific dissection of whole pieces of music to understand their structure and how the parts fit together). When I moved to science, that kind of analytical thought process jumped to the fore. Science is a lot of hard work, even repetitive work, which is similar to what I did in music. But you intersperse that with periods where you’re talking to people and thinking about things. When I started out, I’d pipette for a few hours, then have a break while samples were incubating or a gel was running, and that’s the time when you get to just exchange ideas with people. I think that social side of science is very important. And it provided a lot more variety than I was getting from playing the same pieces over and over again, just so that my fingers would stay in shape. How music helped researchMusic gave me an appreciation for things that were done a very long time ago, and the importance of trying to dig into these things. When I started out in science, I remember thinking how recent the references were. Whereas musical theorists might cite Johann Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum, which is a treatise on counterpoint that influenced Bach, Beethoven and other composers, and dates back to 1725, biologists rarely cited anything that old. But there’s a long history to the kind of work we do today. For instance, we combined some old methods that biologist Karl Landsteiner developed in the early twentieth century with newer techniques to discover how T cells help to select the best antibodies in structures called germinal centres. Another aspect of my musical career that I continue to apply in the way I do science is that habit of just practising something over and over. The way you learn a piece of music is to practise. It shouldn’t matter that you’re bad at it at first: what matters is that you’re beginning something that’s very difficult and working on it until it becomes easy. You’ll become good at it at some point. The effort you put into it is what enables you to do challenging things. I use this approach a lot in science, and I encourage my trainees to do so, too. Difficult protocols and techniques, for example — they all benefit from many tries until you get the hang of them. A lot of the work, both in science and music, is just being willing to try something, fail repeatedly, and not take no for an answer. Adapted from an interview of Gabriel Victora by Jyoti Madhusoodanan in Nature.

Images: Screengrab from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8al3rdxZj0&t=189s. Overlay: https://bit.ly/3Eh76HM We live in the era of efficiency. We want our teams to be lean. Our processes to be agile. And our output to be optimised. Instead of maximising our impact, we aim to minimise our waste. In the search to remove redundancy, marketing perceives paid social media and online video as cheap, able to reach defined audience and provide measurable response. Traditional broadcast communications are thought to be an inconceivable indulgence: they are mass, ignored and expensive. This article argues that efficient doesn’t necessarily mean effective, that more productive doesn’t necessarily mean more powerful, and that being mass, ignored and expensive are not points of weakness but, in fact, points of strength. Error 01: Mass media is wasteful because it is untargetedWhen you communicate on mass media, whether it’s a 30-second spot on prime-time TV, a press ad in a national newspaper, or a 6-sheet in a city centre, you will reach a large number of those who are in your target market. But you will also reach a large number of those who are not. Imagine, for example, that you’re advertising a luxury car. Broadcast communications will inevitably reach those who are too young to drive, those who are too old, those who don’t have a driver’s license, those who rely on public transport, those who are banned from driving and those who can’t afford a premium vehicle. But considering these segments to be ‘waste’ ignores one the most foundational roles that brands perform. It ignores the idea that brands not only provide functional and emotional benefits, but self-expressive ones. By driving an expensive brand of car, the owner communicates their financial status. The car’s design might communicate their sense of style. And its provenance might communicate their sensibilities. The fact that everybody understands what the brand represents makes it a more effective signal of what the buyer represents. Advertising to those who cannot afford the brand makes the product more appealing to those who can. For a potential audience to buy the brand, they have to know that a much wider audience aspires to do the same. Traditional broadcast communications not only reach a large audience, they reach that audience publicly. In mass media, not only do many people see your advert, but they see many other people see your advert as well. When you broadcast your brand, everybody knows that everybody else knows what you stand for. To summarise, yes traditional communications are mass, but that does not make them wasteful. Mass media reaches a large audience, imprinting brands on culture and imbuing them with self-expressive benefits. Error 02: Mass media is wasteful because it is ignored'It’s easy to see how low-attention communication channels could be seen to be inefficient. If two-thirds of each TV ad doesn’t receive active attention, isn’t that two-thirds of spend that is wasted? A group of contrarian researchers believes that the answer is no. The academics argue that when it comes to brand building, low attention equals high value. In 1964, Leon Festinger partnered with his colleague Nathan Maccoby to understand how people process messages during periods of distraction. A summary of the experiment appears in the book, The Choice Factory: “Festinger and Nathan Maccoby, academics at Stanford University, recruited members of college fraternities. They played those students an audio argument about why fraternities were morally wrong. The recording was played in two different scenarios: students either heard it on its own or they watched a silent film at the same time. After the students had heard the recording, the Stanford psychologists questioned them as to how far their views had shifted. Those who had heard the argument at the same time as the silent film were more likely to have changed their opinion." The silent film provided a distraction which reduced the level of attention that was applied to the audio argument. But rather than decrease the argument’s potency, it increased its power. The psychologists hypothesised that participants in the undistracted, high-attention group were able to generate counter-arguments that maintained their existing opinions and avoided the discomfort of experiencing cognitive dissonance. In the low-attention group, on the other hand, the participant's cognitive defences were not invoked and their ability to counter-argue hampered. [Paul Feldwick, author of The Anatomy of Humbug: how to think differently about advertising] summarises the argument beautifully: "When we don’t notice we are being influenced, we cannot argue back." Dr. Robert Heath, author of Seducing the Subconscious summarises: “My theory is that the most successful advertising campaigns in the world are not those we love or those we hate, or those with messages that are new or interesting. They are those (…) that are able to effortlessly slip things under our radar and influence our behaviour without us ever really knowing that they have done so. And the way in which these apparently inoffensive ad campaigns work is by 'seducing' our subconscious.” Michael Shudson, author of Advertising: The Uneasy Persuasion, concludes: “Ads may be more powerful precisely because people pay them so little heed that they do not call critical defences into play.” Error 03: Mass media is wasteful because it is expensiveDarwin’s theory of evolution stated that small mutations made individual animals more or less suited to their environment. Those whose traits benefited them would be more likely to survive, whilst those whose variations hindered them would fall foul of the opposite fate. Over time, species would evolve, converging towards an optimal set of natural abilities. But one thing puzzled Darwin. Why have some animals evolved with attributes that seem to have no functional utility? Why do some, even, have attributes that seem to hinder, not help, their survival. Darwin soon found his answer. He realised that evolution relied not just on which animals survived, but also on those which reproduced. Darwin deduced that the traits that he had perceived to be impediments to survival, were actually advantages when it came to sexual selection. Those who prospered despite their physical encumbrances, he believed, must be stronger, and thus more attractive mates. Or to put it another way, sexual partners deduce that the animals who waste resources must have enough resources to waste. But how does the field of biology relate to the world of business? In 2004 the marketing icon Tim Ambler published a landmark paper in The Journal of Advertising Research that drew a direct connection between the way that animals and brands signal their strength. Both, he argued, communicated through conspicuous waste: “Evidently, just as a female peacocks are drawn to mate with the largest, most spectacular tail feathers because the display signals superior biological fitness, consumers are attracted to brands that invest in lavish displays like Super Bowl commercials because such extravagance signals a high-quality, successful brand.” Ambler hypothesised that just as animals signalled their strength through unnecessary adornment, brands signalled their strength through unnecessary spend. The extravagant spend is to the brand what the plumage is to the peacock. It is its very inefficiency that makes it effective. Expensive media signals brand strength. Inefficient communication carries a “costly signal” that the brand being advertised is of high quality, that it is in strong financial shape, and that it is likely to continue being strong and successful for the foreseeable future. To test this theory, Thinkbox asked over 3,500 people if they perceived brands to be “high quality”, “financially strong” and “confident” when seeing them advertised in various media channels. TV, the archetypal expensive media channel, scored 43%, 50% and 58% respectively. Social media, on the other hand, scored significantly lower at 19%, 21% and 40%. The research suggests a broader truth. On every single metric expensive, traditional media (TV, newspapers, magazines and radio) outperformed cost-efficient digital channels (social media and video sharing sites). Rory Sutherland sums up in Alchemy: “The potency and meaningfulness of communication is in direct proportion to the costliness of its creation (…). This may be inefficient – but it’s what makes it work.” Just as a peacock’s plumage signals strength, and the battlements of British banks signal trustworthiness, expensive media signals the same for brands. Broadcast communications cannot target specific segments. But they can imprint brands on culture and imbue them with self-expressive benefits. Mass media cannot command the most attention. But it can bypass an audiences’ cognitive defences and lodge a brand in the audience’s long-term memory. Traditional channels cannot compete when it comes to cost. But they can use expensive media to signal the strength, security and stability of the brands that advertise on them. As Tim Ambler famously put it: “The waste in advertising is the part that works.” Adapted from the article The Errors of Efficiency by Alex Murrell accessed at https://www.alexmurrell.co.uk/articles/the-errors-of-efficiency

Image: https://cliparting.com/free-peacock-clipart-32777/ “People don’t know how ordinary success is,” said Mary T. Meagher, winner of three gold medals in the Los Angeles Olympics, when asked what the public least understands about her sport. When Mary T. Meagher was 13 years old and had qualified for the National Championships, she decided to try to break the world record in the 200-Meter Butterfly race. She made two immediate qualitative changes in her routine: first, she began coming on time to all practices. She recalls now, years later, being picked up at school by her mother and driving (rather quickly) through the streets of Louisville, Kentucky, trying desperately to make it to the pool on time. That habit, that discipline, she now says, gave her the sense that every minute of practice time counted. And second, she began doing all of her turns, during those practices, correctly, in strict accordance with the competitive rules. Most swimmers don’t do this; they turn rather casually, and tend to touch with one hand instead of two (in the butterfly, Meagher’s stroke). This, she says, accustomed her to doing things one step better than those around her—always. Those are the two major changes she made in her training, as she remembers it. "I never looked beyond the next year, and I never looked beyond the next level. I never thought about the Olympics when I was ten; at that time I was thinking about the State Championships. When I made cuts for Regionals [the next higher level of competition], I started thinking about Regionals; when I made cuts for National Junior Olympics, I started thinking about National Junior Olympics . . . I can’t even think about the [1988] Olympics right now. . . . Things can overwhelm you if you think too far ahead." In the pursuit of excellence, maintaining mundanity is the key psychological challenge. In common parlance, winners don’t choke. Faced with what seems to be a tremendous challenge or a strikingly unusual event, such as the Olympic Games, the better athletes take it as a normal, manageable situation...and do what is necessary to deal with it. Source: https://academics.hamilton.edu/documents/themundanityofexcellence.pdf

Image: https://alchetron.com/cdn/mary-t-meagher-41561f59-ac05-4f52-8a92-b39693da3d1-resize-750.jpeg WHEN BARTLEBY reflects on life’s lessons, he always remembers his grandfather’s last words: “A truck!” Bartleby’s uncle also suffered an early demise, falling into a vat of polish at the furniture factory. It was a terrible end but a lovely finish. Whether you find such stories amusing will depend on taste and whether you have heard them before. But a sense of humour is, by and large, a useful thing to have in life. A study of undergraduates found that those with a strong sense of humour experienced less stress and anxiety than those without it. Humour can be a particular source of comfort at work, where sometimes it can be the only healthy reaction to setbacks or irrational commands from the boss. The comedy stems, in part, from the way that the office hierarchy requires the employees to put up with the appalling behaviour of the manager. The healthiest kind of workplace humour stems from the bottom up, not from the top down. Often the most popular employees at work are those who can lighten the mood with a joke or two. Zoom has zapped humourA downside of remote working is that moments of shared humour are harder to create. Many a long meeting at The Economist has been enlivened by a subversive quip from a participant. These jokes only work when they are spontaneous and well-timed. Trying to make a joke during a Zoom conference call is virtually impossible; by the time one has found the “raise hand” button and been recognised by the host, the moment has inevitably passed. This is a shame, as most of us could do with a laugh now and again to get through the pandemic. Work is a serious matter but it cannot be taken seriously all the time. Sometimes things happen at work that are inherently ridiculous. Perhaps the technology breaks down just as the boss is in mid-oration, or a customer makes an absurd request. (Remember the probably apocryphal story of a person who rang the equipment manufacturer and asked them to fax through some more paper when the machine ran out?) There is also something deeply silly about management jargon. Most people will have sat through presentations by executives who insist on calling a spade a “manual horticultural implement”. Too many managers use long words to disguise the fact they have no coherent message to impart. Such language is ripe for satire or at the very least a collective game of “buzzword bingo”. Adapted from The Economist, October 3, 2020.

There are emotive reasons why covid-19 might make countries less willing to accept foreigners even after a vaccine is discovered and the pandemic is suppressed. People are scared: not only of this pandemic but also of the next. Many associate foreigners with disease. Many voters believe that migrants take jobs from the native-born, and so would keep curbs on immigration even after other travel restrictions are loosened. Both these fears are electorally potent, but neither is well-founded. Tourists and business travellers vastly outnumber migrants. When it is possible to open borders to short-term travellers, it should also be possible to open them for migrants. Unlike tourists, people who plan to stay for years will not object to a two-week quarantine on arrival. The precautions that work best—social distancing, contact-tracing, handwashing and testing—pay no heed to nationality. Nor does the virus. The idea that more migrants means fewer jobs for locals in the long run is an example of the fallacy that the economy has a fixed “lump of labour”. As well as spending their wages, which supports new jobs, migrants bring a greater diversity of skills to the workforce, allowing the labour market as a whole to operate more efficiently. They make WFH safer and more productiveHowever, even as covid-19 has immobilised the world, it is making some people appreciate the benefits of mobility. Many voters in rich countries have noticed that doctors are often migrants: 53% in Australia, 29% in America. The same is true of nurses, care-home workers and virus-busting mop-wielders. When people bang pots for health-care workers, they applaud a lot of foreigners. Migrants are also over-represented among those who make it possible for others to work safely and productively at home, by harvesting and processing food, delivering parcels and fixing software bugs. They turbocharge innovation, too. Some 40% of medical and life scientists in America are foreign-born. Vaccine research depends on large teams of talents from all around the world. Half the big American tech firms were founded by a first- or second-generation immigrant. If the founder of Zoom had never left China, locked-down professionals might not even know what their colleagues’ bookshelves look like. When the coronavirus is vanquished, migration will still be what it was before: a powerful tool that can lift up the poor, rejuvenate rich countries and spread new ideas around the world. A pandemic is no reason to abandon it. Adapted from The Economist, August 1, 2020.

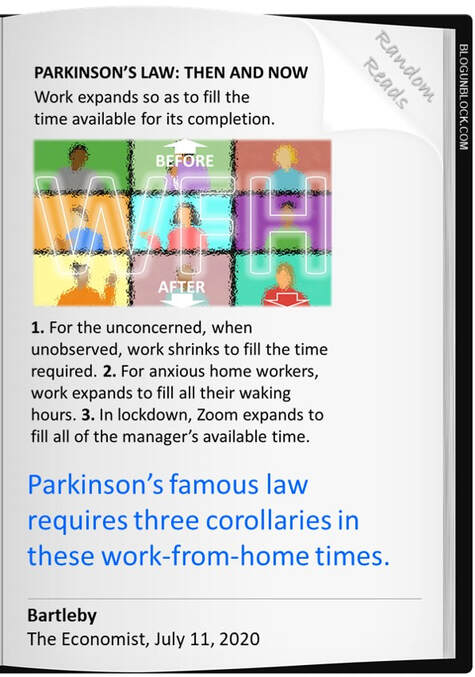

AS LAWS GO, the dictum devised by C. Northcote Parkinson, a naval historian, was admirably succinct: “Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” His essay, first published in The Economist in 1955, has stood the test of time, in the sense that people still refer to “Parkinson’s law”. But the experience of working life during the pandemic [necessitates] three corollaries to the theorem. When it comes to office work, the incentives to dawdle are pretty clear. Finish an assignment quickly, and the employee will just be given another. That second task may be even more unpleasant than the first. Workers may end up like a hamster on a treadmill, stuck in an endless cycle of needless effort. Office workers know, however, that the mission itself is not the only thing. It is important to be seen to be working. This leads to “presenteeism”—being at your desk for long enough to impress the boss (and even turning up while sick). In the pre-internet era this would involve endless redrafting of memos, long phone calls, or staring meaningfully at documents. Thanks to the pioneering work of Tim Berners-Lee, presenteeism now requires less effort: many hours can be wasted on the world wide web. When working at home, the boss is out of sight but not out of mind. Broadly speaking, the result is to divide workers into two factions. The first group, the slackers, has spent the lockdown working out the minimum level of effort they can get away with. They have no need to drag out each task; they do what is required and spend the rest of the day at leisure, submitting the work just before deadline. For this group, Parkinson’s law can be amended as follows: “For the unconcerned, when unobserved, work shrinks to fill the time required.” The second group takes the opposite approach. Consumed by guilt, anxiety about their job security or ambition, they work even harder than before. Being at home, they find no clear demarcation between work time and leisure time. They require their own amendment: “For anxious home workers, work expands to fill all their waking hours.” Like their staff, managers also want to appear useful. In the office, they can seem busy by walking around and talking to their teams. At home, this is more difficult; a phone call is more intrusive than a casual chat. The answer is to organise more Zoom meetings. Hence the third amendment to his law: “In lockdown, Zoom expands to fill all of the manager’s available time.” Adapted from Parkinson’s Law Updated, from the Bartleby column in The Economist, July 11, 2020 edition. © The Economist Group Limited, London 2020.

|

Vijayakumar Kotteri

Abstracts from works of different authors. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed