|

The immersion of the individual in the routine of life causes him to be seriously disturbed by the sudden experience of death, particularly when it takes away someone who has been near and dear to him. When the sight of death becomes too frequent, as in times of war or during an epidemic, the individual’s mind tends to protect itself by retiring within a shell of habit and routine. Familiar actions, faces and surroundings, which require no thoughts or adjustment, become at such times a buttress to his emotional balance. But even this wall of cultivated indifference crumbles when the hand of death snatches away someone who has entered deeply into his inner life—someone who perhaps acted as a pivotal point upon which his emotions turned. At such a time, his unquestioning attitude towards life is disturbed and his mind becomes deeply preoccupied with an intensive search for lasting values. As the tale of life is told it pauses frequently to contemplate the gaping holes left by death. There is no way to avoid the thought-provoking impact of that inescapable presence. When a sensitive individual is first faced by a death of deep significance in his circle of close friends, he is usually struck by the transitory nature of all forms of life. Confronted by the undeniable impermanence of the body, yet unfortified by knowledge of some sustaining permanent principle, he often falls into a mood of deep despair or supercilious cynicism. Vanishing existence, permanent extinctionIf life is inexorably doomed to extinction, he reasons, there can be little meaning in frantic efforts to achieve. In turn, this thought leaves him in a vacuum of purpose which may lead him either to a state of supine inaction or may precipitate him into reckless rebellion. To him, existence seems to be conditional, intermittent and vanishing, while extinction appears to be unqualified, inescapable and permanent. In short, if death is looked upon as mere extinction, man tends to lose his balance and is plunged into perpetual gloom. All his dreams of the enduring reality of truth, beauty and love are refuted and seem by hindsight to have been a blind groping after illusion. His previous ideal of eternal and inexhaustible sweetness, instead of filling him with hope and enthusiasm, now reproaches him with the utter senselessness of all earthly values. Thus death, when not understood, vitiates the whole of life, and the first impulsive answer of inaction or cynicism, which the individual usually forges to meet the question, strands him in a thoroughly desiccated universe of unrelieved weariness. Nevertheless, this gradually prepares him for another attempt to find a more vital answer to the inescapable query. The human mind cannot endure such a stalemate for long, as there is an internal force which insists that the inner nature be in motion. Eventually, the pressure for such motion breaks through the rigidity of such a negative concept of death, a great flood of new interrogation and discovery often breaks out, and in it the key question now posed by death becomes “What is life?” To understand death, understand lifeThe answers supplied are countless, and depend upon the passing moods which spring from the deeply rooted ignorance of the interrogator. The first instinctive answer is “Life is that which is terminated by death.” This answer is still completely inadequate, as it involves no positive principle on which a fruitful life can be based, nor can the individual’s need for development be met. Such an answer explains neither life nor death. The individual is driven to try to understand life and death along new lines. Instead of looking upon death as the opposite of life, he now inevitably comes to look upon it as the handmaiden of life. He begins to affirm intuitively the reality and the eternality of life. Instead of interpreting life in terms of death, man seeks to interpret death in terms of life. Slowly, event by event, he learns to take life again in all earnestness, with a deeper affirming consciousness. As he does so, he is able to give a more constructive response to the recurring site of death. The challenge of death is now not only accepted and absorbed by life, but is met by a counter-challenge: ”What is death?” It is now death’s turn to submit itself to critical scrutiny. The most unsophisticated answer to this counter-question is, “Death is only an incident in life”. This simple and profoundly true declaration terminates the unendurable chaos precipitated by regarding death as the extinction of life. Soon, it is clearly seen that it is futile to try to understand death without first understanding life. As consciousness gradually settles into this balanced approach to the problem, it takes on a healthy tone which makes it receptive to the truth concerning both life and death. Direct, undimmed knowledge of such truth is available only to spiritually advanced souls. The seers of all times have had direct access to the truth about life and death, and they have repeatedly given a suffering and groping humanity useful information on this point. Their explanations are important because they protect man’s mind from erroneous and harmful attitudes towards life and death, and prepare him for perception of the truth. Although direct knowledge of truth requires considerable spiritual perception, nevertheless even correct intellectual understanding of the relationships of life and death plays an important part in restoring mankind to a healthy outlook.

0 Comments

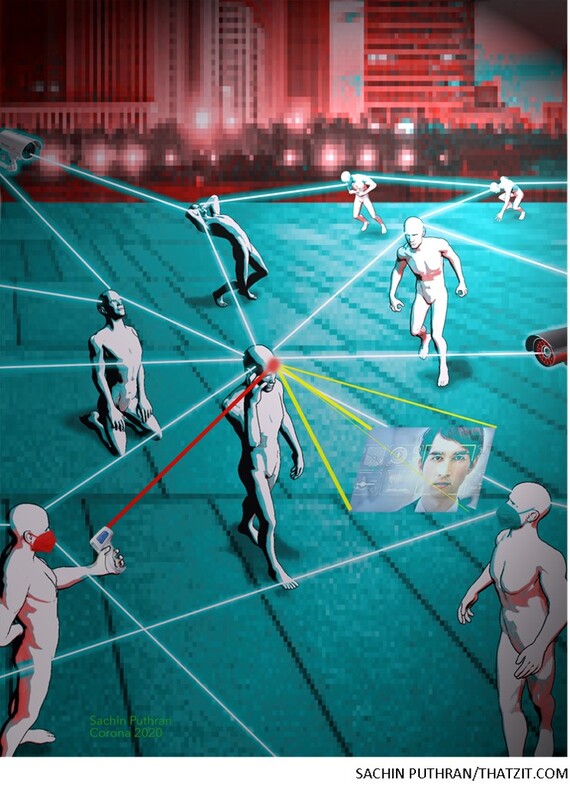

Humankind is now facing a global crisis. Perhaps the biggest crisis of our generation. The decisions people and governments take in the next few weeks will probably shape the world for years to come. We must act quickly and decisively. When choosing between alternatives, we should ask ourselves not only how to overcome the immediate threat, but also what kind of world we will inhabit once the storm passes. Many short-term emergency measures will become a fixture of life. That is the nature of emergencies. They fast-forward historical processes. Decisions that in normal times could take years of deliberation are passed in a matter of hours. Immature and even dangerous technologies are pressed into service, because the risks of doing nothing are bigger. Entire countries serve as guinea-pigs in large-scale social experiments. What happens when everybody works from home and communicates only at a distance? What happens when entire schools and universities go online? In normal times, governments, businesses and educational boards would never agree to conduct such experiments. But these aren’t normal times. In this time of crisis, we face two particularly important choices. The first is between totalitarian surveillance and citizen empowerment. The second is between nationalist isolation and global solidarity. Under-the-skin surveillanceIn order to stop the epidemic, entire populations need to comply with certain guidelines. There are two main ways of achieving this. One method is for the government to monitor people, and punish those who break the rules. Today, for the first time in human history, technology makes it possible to monitor everyone all the time. In their battle against the coronavirus epidemic several governments have already deployed the new surveillance tools. The most notable case is China. By closely monitoring people’s smartphones, making use of hundreds of millions of face-recognising cameras, and obliging people to check and report their body temperature and medical condition, the Chinese authorities can not only quickly identify suspected coronavirus carriers, but also track their movements and identify anyone they came into contact with. A range of mobile apps warn citizens about their proximity to infected patients. You might argue that there is nothing new about all this. In recent years both governments and corporations have been using ever more sophisticated technologies to track, monitor and manipulate people. Yet if we are not careful, the epidemic might nevertheless mark an important watershed in the history of surveillance. Not only because it might normalize the deployment of mass surveillance tools in countries that have so far rejected them, but even more so because it signifies a dramatic transition from “over the skin” to “under the skin” surveillance. Hitherto, when your finger touched the screen of your smartphone and clicked on a link, the government wanted to know what exactly your finger was clicking on. But with coronavirus, the focus of interest shifts. Now the government wants to know the temperature of your finger and the blood-pressure under its skin. The emergency puddingSurveillance technology is developing at breakneck speed, and what seemed science-fiction 10 years ago is today old news. If corporations and governments start harvesting our biometric data en masse, they can get to know us far better than we know ourselves, and they can then not just predict our feelings but also manipulate our feelings and sell us anything they want — be it a product or a politician. Even when infections from coronavirus are down to zero, some data-hungry governments could argue they needed to keep the biometric surveillance systems in place because they fear a second wave of coronavirus, or because there is a new Ebola strain evolving in central Africa, or because . . . you get the idea. A big battle has been raging in recent years over our privacy. The coronavirus crisis could be the battle’s tipping point. For when people are given a choice between privacy and health, they will usually choose health. The soap policeCentralised monitoring and harsh punishments aren’t the only way to make people comply with beneficial guidelines. Consider, for example, washing your hands with soap. This has been one of the greatest advances ever in human hygiene. This simple action saves millions of lives every year. While we take it for granted, it was only in the 19th century that scientists discovered the importance of washing hands with soap. Previously, even doctors and nurses proceeded from one surgical operation to the next without washing their hands. Today billions of people daily wash their hands, not because they are afraid of the soap police, but rather because they understand the facts. But to achieve such a level of compliance and co-operation, you need trust. People need to trust science, to trust public authorities, and to trust the media. Over the past few years, irresponsible politicians have deliberately undermined trust in science, in public authorities and in the media. Now these same irresponsible politicians might be tempted to take the high road to authoritarianism, arguing that you just cannot trust the public to do the right thing. Instead of building a surveillance regime, it is not too late to rebuild people’s trust in science, in public authorities and in the media. We should definitely make use of new technologies too, but these technologies should empower citizens. The coronavirus epidemic is thus a major test of citizenship. In the days ahead, each one of us should choose to trust scientific data and healthcare experts over unfounded conspiracy theories and self-serving politicians. If we fail to make the right choice, we might find ourselves signing away our most precious freedoms, thinking that this is the only way to safeguard our health. We need a global planThe second important choice we confront is between nationalist isolation and global solidarity. Both the epidemic itself and the resulting economic crisis are global problems. They can be solved effectively only by global co-operation. First and foremost, in order to defeat the virus we need to share information globally. That’s the big advantage of humans over viruses. A coronavirus in China and a coronavirus in the US cannot swap tips about how to infect humans. But China can teach the US many valuable lessons about coronavirus and how to deal with it. What an Italian doctor discovers in Milan in the early morning might well save lives in Tehran by evening. When the UK government hesitates between several policies, it can get advice from the Koreans who have already faced a similar dilemma a month ago. But for this to happen, we need a spirit of global co-operation and trust. Countries should be willing to share information openly and humbly seek advice, and should be able to trust the data and the insights they receive. We also need a global effort to produce and distribute medical equipment, most notably testing kits and respiratory machines. Instead of every country trying to do it locally and hoarding whatever equipment it can get, a co-ordinated global effort could greatly accelerate production and make sure life-saving equipment is distributed more fairly. Just as countries nationalise key industries during a war, the human war against coronavirus may require us to “humanise” the crucial production lines. A rich country with few coronavirus cases should be willing to send precious equipment to a poorer country with many cases, trusting that if and when it subsequently needs help, other countries will come to its assistance. We might consider a similar global effort to pool medical personnel. Countries currently less affected could send medical staff to the worst-hit regions of the world, both in order to help them in their hour of need, and in order to gain valuable experience. If later on the focus of the epidemic shifts, help could start flowing in the opposite direction. Global co-operation is vitally needed on the economic front too. Given the global nature of the economy and of supply chains, if each government does its own thing in complete disregard of the others, the result will be chaos and a deepening crisis. We need a global plan of action, and we need it fast. Another requirement is reaching a global agreement on travel. Suspending all international travel for months will cause tremendous hardships, and hamper the war against coronavirus. Countries need to co-operate in order to allow at least a trickle of essential travellers to continue crossing borders: scientists, doctors, journalists, politicians, businesspeople. This can be done by reaching a global agreement on the pre-screening of travellers by their home country. Unfortunately, at present countries hardly do any of these things. A collective paralysis has gripped the international community. There seem to be no adults in the room. Humanity needs to make a choice. Will we travel down the route of disunity, or will we adopt the path of global solidarity? If we choose disunity, this will not only prolong the crisis, but will probably result in even worse catastrophes in the future. If we choose global solidarity, it will be a victory not only against the coronavirus, but against all future epidemics and crises that might assail humankind in the 21st century. Copyright © Yuval Noah Harari 2020

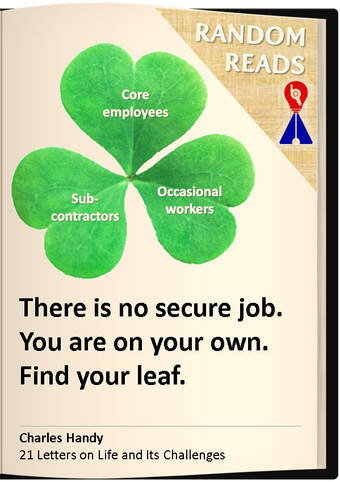

Adapted from the original written by Yuval Noah Harari. Read the complete article here. Yuval Noah Harari is historian, philosopher and the author of Sapiens, Homo Deus and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Sachin Puthran is an artist-entrepreneur, as creative as he is with pencil and paper as he is adept at wielding the latest technology to cater to varied communication needs. While the virus has locked us all at home, the pandemic was not on the horizon when Charles Handy wrote his “21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges”. Yet his thoughts on intangibles like faith, enough and companionship are very relevant today as we pray for us and others, introspect about what matters, and cherish the time with family even as we miss our team. Faith Do you believe in God, or a god, or in anything else? Let no one tell you what to believe about things that are beyond our understanding. They can only be matters of faith and faith is not subject to reason. Indeed, faith begins where reason runs out. My own journey [took me] through faith to the experience of living in comfortable doubt. As Julian Barnes said, “I don’t believe in God, but I miss Him." It was nice in a way to think that there was this person watching over me, even if he was often disapproving. When my reason told me that this was a fanciful concoction, I felt very much alone in the world, left to my own devices, forced to work out for myself what was right and what was wrong. I would not be surprised if you did not also wonder from time to time whether there was not something more than our dull earthly existence, some sense of the numinous or the spiritual that brought out the best in us. That, to me, is what prayer is: asking myself if I am yet in the fullness of my being. Wendell Berry, the wonderful farmer poet from Kentucky, puts it well at the end of one of his poems: And we pray, not for new earth or heaven, but to be quiet in heart, and in eye clear. What we need is here. Laws define what you can and can’t do but don’t tell you what you should do. That is the sphere of ethics. A good society would be one in which there was a common understanding of what was right and proper in human relationships. Newer generations are beginning to set out their own guidelines, spread through social media, a development that can lead to relativism and a divergent society, with different groups asserting different values and priorities. If such a fluid society of mixed values emerges it becomes critical that each individual forms his or her own set of moral standards rather than going with the values of whatever gang or group attracts their loyalty. I started this letter with God. I ended it with You. I think they are the same. God is shorthand for the Goodness in You. Enough In 1930 John Maynard Keynes, the great economist, suggested that for his grandchildren the economic problem would be solved, by which he meant that there would be no more scarcity. Technological and productivity advances would create an economic utopia in which nobody would have to work more than fifteen hours a week; we would all, if everything was fairly distributed, have enough. That worried him because, he said, we have been expressly evolved by nature – with all our impulses and deepest instincts – for the purpose of solving the economic problem. If the economic problem is solved, mankind will be deprived of its traditional purpose. We won’t, in other words, know what to do with ourselves if we no longer have to work all the hours in the week to support ourselves. Keynes was right, but only in theory. As it is, the idea that enough is a good as a feast competes with the other slogan that you can never have enough of a good thing – and the latter often wins. Keynes’s forecast has not yet come true. More people are working more hours than ever before even though they already probably have enough to lead a reasonably comfortable life. Why do we do it? Is it to buy more stuff, or to show how important we are? Or because our colleagues are getting more than us? Whatever the reason we do seem to have an insatiable appetite for more: more things, more money, more entertainment, more everything. Part of the reason, however, must surely be that we love work: not necessarily the actual work itself but everything that goes with it. Work gives many of us our identity. We are what we do. It provides the glue of society, brings people together, shapes our day and gives us a reason to get up in the morning. Our hunter ancestors did not have that urge. Research on the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert showed that the idea that our prehistoric ancestors had a hard life of unremitting toil was not true. They only worked when they had to, did not store food, had few wants, which were easily satisfied. They only had to take up their spears and go hunting when more was food was needed. As a result, they worked only fifteen hours a week. There would have been no point in working more. Some have called them ‘the first affluent society’. The missing ingredient, however, was money. Had the Bushmen had money or other means of exchange their lives might have been less leisured. Perhaps the love of money really was the root of all evil. My wife and I, however, were not collectors. Each year, during my working career, we would calculate how many money-making contracts to speak or teach or write I needed to undertake in order to make sure that we would have enough; enough, that is, to enable us to live relatively comfortable lives. We soon realised that the lower we set the bar for enough the more freedom we had to do all the other things. Blessed are the poor, you could say, provided always that you are poor by choice and not necessity. Along with many others, I have found that the work I do for free is much more satisfying that the work I do or did for money to support my family. By work for free I include not only work for charities or good causes, but also the work I do at home: cooking, entertaining, caring for children – including you – fixing things that go wrong. I love cooking but after a day at the chopping board I know that it is work as well as pleasure. The idea of enough is not confined to money and work. It works in every part of life. Food and drink, most obviously, where enough is literally as good as a feast. There is also the temptation to concentrate on some subject or activity to the exclusion of anything else. That runs the risk of what economists call opportunity cost, when you miss out on the opportunity of developing an alternative interest or activity. One year, when I was totally absorbed in my work, my wife told me that I had become the most boring man she knew. By ignoring the rule of enough I had narrowed my life and might have ruined my marriage. Companionship I hope that you will be lucky enough to go through life saying “we” more often than “I”. Companionship is so important, to have someone with whom you can share your hopes and uncertainties. It does not have to be a life partner. It can be your family, a work group or a whole organisation, even a movement. What people don’t tell you, however, is that to enjoy the undoubted benefits of “we” in any relationship, be it a partnership, a close friendship or a work group, you have to first invest in it. There can be no free ride in a true togetherness. To get you first have to give, and you can only give if you care, and, ideally, care more for the other than yourself. The poet Philip Larkin put it well: We should be careful Of each other, we should be kind While there is still time. Kindness is the glue of friendship. You can argue with a friend, disagree with their political or religious views, as long as you do it kindly, respecting their right to disagree with you. The “we” carries over into the workplace, even when it isn’t an actual place. When I did a study of entrepreneurs they all agreed that they could not have done it on their own, even if they were the ones who had the original idea. I have already argued that small is best but for small to work the groups have to be teams. Teams are groups with a shared purpose in which each member has their own individual contribution to make. They are a looser form of friendship but function best when there is a real commitment to a shared purpose and a respect for each other’s contribution. Individuals are chosen for their individual contribution but have to work closely together or the whole does not work. No one is too good not to need to learn. Small groups, changing leadership, a common focus and a clear objective: it is a recipe for excellence. Note, too, the role of the outside coach and the regular briefing sessions. No one is so good that they have no need of an outside perspective, nor should any activity go without regular reviews. It is a comradeship based on trust and shared interests. If you find yourself in such a group you will be fortunate. Perhaps you only know how special someone or something is when you have lost it. So, it is with friendship. Never take it for granted. Cherish those special friends. You will miss them if they go. All text in this post is adapted from the book "21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges" written by Charles Handy. Copyright © Charles Handy 2019. Published by Hutchinson, a part of Penguin Random House. Charles Handy has written this book for his four grandchildren. In the Introduction to the book, he writes:

"You are living in a very different world to the one I knew, but I suspect that the issues you come up against will not be that dissimilar. It is hard to learn from other people’s experiences, but my reflections may make you at least pause and think before you act, or, sometimes, think again after you have acted. These letters, you might say, contain all the stuff that I wished I had known when I was your age, before I went out into the world and had to make my own future, my own contract with life.” Charles Handy CBE (born 1932) is an independent Irish writer, broadcaster, teacher and philosopher specialising in organisational behaviour and management. He has been an oil executive, an economist, a professor at the London Business School, the Warden of St. George’s House in Windsor Castle and the chairman of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. He has been rated among the Thinkers 50, a private list of the most influential living management thinkers. All faiths are a gift of God, but partake of human imperfection, as they pass through the medium of humanity. God-given religion is beyond all speech. Imperfect men put it into such language as they can command, and their words are interpreted by other men equally imperfect. Whose interpretation must be held to be the right one? Everyone is right from his own standpoint, but it is not impossible that everyone is wrong. Hence the necessity for tolerance, which does not mean indifference towards one's own faith, but a more intelligent and purer love for it.... True knowledge of religion breaks down the barriers between faith and faith and gives rise to tolerance. Cultivation of tolerance for other faiths will impart to us a truer understanding of our own.

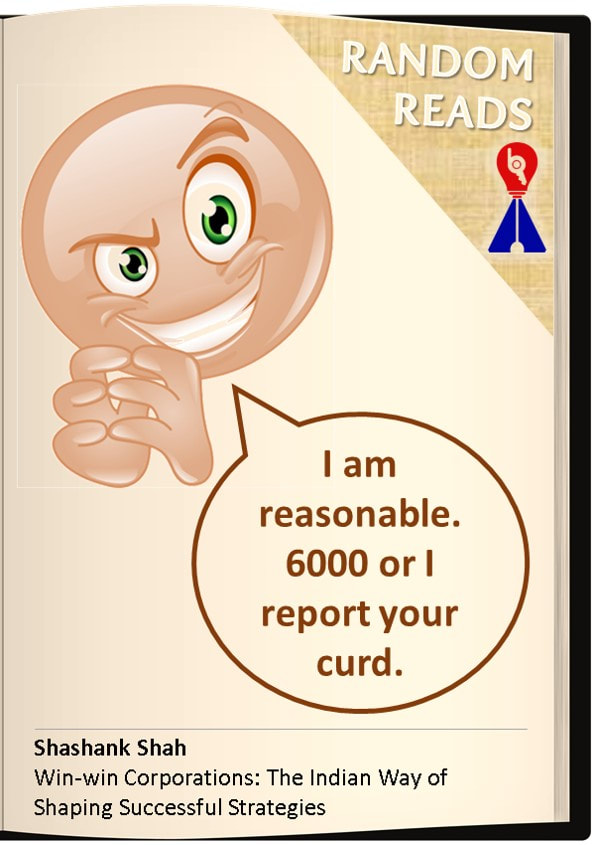

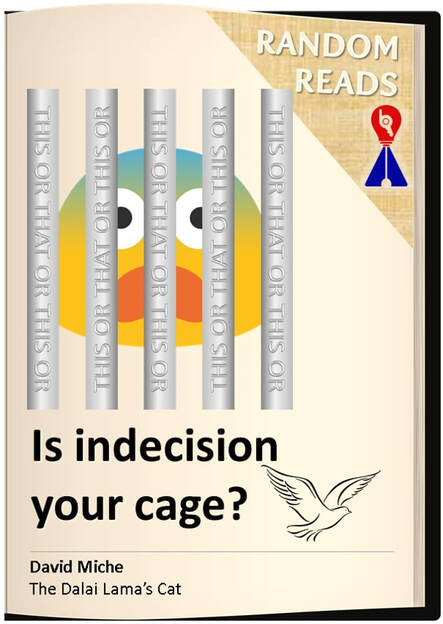

Let’s go back two decades to one of the Taj properties in Kerala. One Sunday morning, a food inspector arrived at the hotel and approached the deputy general manager (DGM) with his intention to inspect the premises. He was promptly invited into the kitchens for his checks. However, he was hesitant. Instead, he said, “If you insist I’ll check. But I am a reasonable person and don’t like to create trouble.” The DGM knew where he was heading and so he said, “You’re most welcome to join us for lunch.” The inspector declined the offer saying he didn’t have time and had to leave at the earliest. After a lot of back and forth he said, “You give me ₹6,000 and I’ll leave.” The DGM flatly refused. He said, “I will not, I cannot.” The inspector threatened him with serious repercussions and said that he could put the hotel in trouble. Concerned with his attitude, the DGM shared the matter with the GM. But the answer remained the same—the inspector was welcome to do whatever assessment he wanted and satisfy himself. Low on fatFinally, he entered the kitchen and went straight to the yogurt section to check the quality. The chef was very happy, because the practice at the Taj was that after buying milk, milk powder was added to it to ensure that the curd set very well. So there was no question of any problem. Yet, surprisingly, the inspector’s report indicated that the fat percentage in the curd was lower by 2.4 per cent. Now the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954, is a non-bailable offence. A GM could go to jail if his hotel was found guilty, and nobody except the chief minister of the state had the authority to save him. So the inspector slapped those charges against the Taj hotel. With a villainous smile he said, “All I was asking for was ₹6,000. I told you, I’m a reasonable man. But you didn’t want to listen.” Over to the courtsNow the hotel had to approach lawyers to defend the case. In those days, a lawyer charged ₹10,000 as appearance fees. On the first appearance, the inspector intentionally didn’t turn up at the court. The second time he came without his file and apologized. The third time he came, but made some other excuse. Now, this had cost the hotel over ₹30,000 simply in legal charges. Finally, the GM decided to go and personally meet the chief minister of Kerala in Thiruvananthapuram. In those days, the Taj did not have a property in Thiruvananthapuram. And so the GM and DGM had to stay in another hotel for two days. That amounted to ₹8,000 per day plus meals and travel costs. Finally, when the GM met the chief minister, he was surprised at a case filed against the Taj. “What is this case? How can there be a food adulteration case against the Taj! I myself eat at the Taj hotels,” he said. Realizing the ridiculousness of the case, he instantly squashed the inspector’s order. The real outputAfter that day, that inspector never came back to any of the Taj hotels in Kerala, because he knew it was a waste of his time. He knew that every time he would come and level wrong charges against the Taj, he would get called to the court, and his “earning time” would get wasted in legal hassles. Thereafter, he would always tell his peers, “Tata ka hotel hai—chhodo.” (It’s Tata hotel, leave it.) A permanent behavioural change was made possible. That was the real output of the ₹50,000 investment by the Tatas. A tall, slim Tibetan Buddhist monk in his mid-30s, Lobsang was originally from Bhutan, where he was a distant relative of the royal family. He had received a thoroughly Western education in America, graduating from Yale with a degree in Philosophy of Language and Semiotics. Lobsang was also the unofficial head of information technology at Jokhang. Whenever computers were uncooperative, printers turned surly, or satellite receiver boxes switched to passive-aggressive mode, it was Lobsang who was called upon to apply his calm, incisive logic to the problem. After the main modem went on the blink, Raj Goel, technical support services representative of Dharamsala Telecom arrived, looking extremely disgruntled. Face set to a scowl, his manner brusque, he demanded to be shown the modem and the telephone lines coming into Jokhang. Slamming his metal briefcase on a shelving unit with an angry crash, he flicked open the clasps, extracted a flashlight and a screwdriver, and was soon poking and prodding a tangle of cables, while Lobsang stood a few feet away, calmly attentive. Grunting as he got to his knees and followed a particular cable to the back of the modem, the technician muttered darkly about systems integrity, interference, and other arcane matters before seizing the modem angrily, tugging a number of cables at the back, and turning it over in his hands. “I’m going to have to open this,” the technician told Lobsang in an accusatory tone. His Holiness’s translator nodded. “Okay.” Rummaging in his briefcase for a smaller screwdriver, Raj Goel began working on the case of the offending modem. “No time for religion.” Was he speaking to himself? His voice seemed too bold for that. “Superstitious nonsense,” he complained a few moments later, even louder. Lobsang was untroubled by the remarks. If anything, a smile seemed to have appeared on his lips. But Raj was spoiling for a fight. Battling with an unyielding screw as he leaned over the modem, this time he spoke in a tone that demanded a response. “What’s the point of filling people’s heads with silly beliefs?” “I agree,” Lobsang replied. “No point at all.” After a pause, [Lobsang] continued. “One of the last things Buddha said to his followers was that anyone who believed a word he had taught them was a fool—unless they had tested it against their own experience.” Patches of sweat began appearing on the technician’s polyester shirt. Lobsang’s reaction was not the one he was after. “Sneaky words,” he groused. “I see people bowing down to Buddhas in temples. Chanting prayers. What’s that if it isn’t blind faith?” Intention matters “Before I answer that, let me ask you something.” Lobsang leaned against the door frame. “Two calls come in during the morning: one from a customer who accidently overturned a filing cabinet onto his modem, the other from a customer who got so angry with his wife for shopping online that he smashed their modem with a hammer. In both cases, the modems are broken and need to be repaired or replaced. Do you treat both customers the same?” “Of course not!” scowled Raj. “What has that got to do with bowing and scraping to Buddhas?” “Quite a lot.” Lobsang’s easy poise couldn’t have contrasted more starkly with Raj Goel's prickliness. “I’ll explain why. But those two customers—” “One was an accident,” the technician interjected, his voice rising. “The other was a deliberate act of vandalism.” “What you’re saying is that intention is more important that an action itself?” “Of course.” “So, when a person bows down to a Buddha, what really matters is the intention, not the bowing?” It was at this point that the technical support services representative began to realize he had blustered his way into a corner. Not that he was about to back out. “The intention is obvious,” he argued. Lobsang shrugged. “You tell me.” “The intention is that you are begging Buddha for forgiveness. You are hoping for salvation.” Lobsang said after a while, “Enlightened beings cannot take away your suffering or give you happiness. If they could do this, wouldn’t they have done so already?” “Then why do you bother?” The technician was shaking his head as he fiddled with the modem. “As you have already said, the intention is important. The statue of Buddha represents a state of enlightenment. Buddhas don’t need people to bow down to them. Why should they care? When we bow, we are reminding ourselves that our own natural potential is one of enlightenment.” The technician finished his work. On the way back down the corridor, as they passed Lobsang’s office, the translator said, “I have something here that may be of interest.” He ducked inside and took a book from one of the bookshelves lining the walls: The Quantum and the Lotus. Raj read the title before flicking the book open. “You can borrow it if you like.” There was an inscription on the title page from one of the book’s authors, Matthieu Ricard. “It’s signed,” noted the visitor. “Matthieu is a friend of mine.” “He has visited Jokhang?” “I first met him in America,” said Lobsang. “I lived there for ten years.” For the first time, Raj looked at Lobsang closely. That revelation was of far greater interest to him than anything else the translator had said. A week later, a more subdued Raj was back, ostensibly to return the book. It turned out that Raj was keen to go to America. He opened up to Lobsang. Parents, job or dream? Once Raj Goel started, there was no stopping him. “I have friends in New York saying, ‘Come and stay with us,’ and I am very keen to do so, because all my life I’ve wanted to visit the Big Apple and earn real dollars and maybe even meet a movie star. But my parents have chosen this girl, you see, and her parents also want us to marry, and they are saying, ‘America will always be there.’ “Also, my boss is pressuring me to go into management development training, but the loan will tie me to the company for six years and I’m feeling trapped. As it is, work pressure is already overwhelming.” He told Lobsang about the agonies of following his friends on Facebook and YouTube as they traveled around America. How his parents thought that a middle-management position with Dharamsala Telecom was the most he could ever aspire to, but he had his own, more entrepreneurial ideas. How his instincts to spread his wings were in constant tension with the loyalty he felt toward his parents, who had made great sacrifices to give him a good education. Finally, the visitor confessed the real purpose of his visit that morning: “I am hoping you can give me some advice to help me reach a decision.” “I don’t have any special wisdom,” said Lobsang, in the way that especially wise practitioners always do. “I have no qualities or realizations. I don’t know why you think I can advise.” “But you lived in America for ten years.” Raj was vehement. “And … ” Lobsang waited for him to finish. “You know about things.” Raj lowered his gaze as though embarrassed to be admitting this, especially to a man whose mental capacity he had questioned only a week earlier. Lobsang simply asked him, “Do you love the girl?” Raj seemed surprised by the question. He shrugged. “I have seen a photograph of her only once. I’m told she wants children, and my parents want us to have children.” “Your friends in America. How long will they be there?” “They have two-year visas. They plan on traveling coast to coast.” “If you want to join them, you must go—?” “Soon.” Lobsang nodded. “What is holding you back?” “My parents,” Raj retorted somewhat sharply, as though Lobsang hadn’t grasped any of what he’d been saying. “The arranged marriage. My boss who wants me to—” “Yes, yes, the management training.” Lobsang’s tone was skeptical. “Why do you say it like that?” “Like what?” “Like you don’t really believe me.” “Because I don’t really believe you.” Lobsang’s smile was so compassionate, so gentle, that it was impossible to take offense. “Oh, I believe all you say about the training and the parents and the marriage. I just don’t believe those are the real reasons you feel trapped.” Deep furrows had returned to Raj forehead. But this time they were furrows of perplexity. “I thought you would agree that these are important responsibilities.” “What—because I am a Buddhist monk?” chided Lobsang. “Because I’m a religious person who wants to uphold the status quo? Is that why you sought my advice?” Raj looked abashed. “You are an intelligent, inquisitive young fellow, Raj. You have been presented with the opportunity of a lifetime. A chance to become a man of the world and to get to understand a lot more not only about America but also about yourself. Why would you not seize this opportunity?” Lobsang posed this as a serious question, and it was some time before his visitor answered. “Because I’m scared of what may happen?” “Fear,” said Lobsang. “An instinct that prevents many people from taking actions that they know, deep down inside, would liberate them. Like a bird in a cage whose door has been opened, we are free to go out in search of fulfillment, but fear makes us look for all kinds of reasons not to.” Set to fly Raj Goel stared at the floor for a while before meeting Lobsang’s eyes. “You are right,” he admitted. “The Indian Buddhist guru Shantideva had some wise words on this very subject,” Lobsang said. He began to quote: ‘When crows encounter a dying snake, They will act as though they were eagles. Likewise, if my self-confidence is weak, I shall be injured by the slightest downfall.' “Now is not the time to be weak or to let your fears overwhelm you, Raj. You may find that if you face your fears head-on, things may not be as bad as you think. Perhaps, after your parents get used to the idea, they won’t be so disappointed. The arranged marriage can wait. Or maybe in two years’ time, there can be a different match. In the meantime, there are many, many things to look forward to. I am sure you will find America an amazing place.” “I know,” Raj Goel said, this time with conviction. Leaning forward in the chair, he picked up his briefcase and practically jumped up with newfound purpose. “You are definitely right! Thank you very much for your advice!” The two men shook hands warmly. “You may even meet a movie star,” suggested Lobsang. About two months after Raj Goel’s visits, the mail brought a glossy postcard of a glamorous female celebrity. It was for Lobsang from Raj. He was now working for one of the biggest phone companies in America. The photo was of a very famous American actress, whose phone Raj had repaired the previous week.

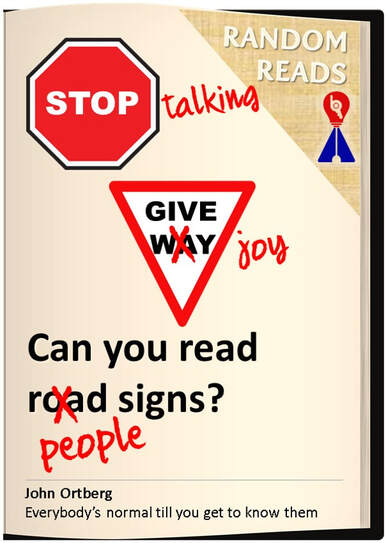

Road signs seek to remove the guesswork out of what you should be doing behind the wheel. What about people signs? What if we had to get licensed before we could start navigating relationships? People could get pulled over by relationship police for talking too fast or too long or too loud, for failure to come to a complete and thoughtful “stop” before executing a proper confrontation, or for trying to merge when all the signs said, “road closed.” It would be a great help if people had signs telling us how to respond to them as we navigate our relational lives. The truth is, they do. But we have to learn how to read them. Is it “Men At Work” or “Emotions At Work”? Is it “Road Closed” or “Heart Closed”? The most common way people send this signal is with their eyes. Eye contact produces strong emotions; in a normal conversation it rarely lasts more than three seconds before one or both people experience a powerful urge to glance away. In your interactions, look for nonverbal stop signs: People start looking away; they stop giving you little verbal cues that say they’re listening; they lean backwards; they stop interacting and asking questions. Stop talking! Give someone else a chance. When we stop talking, we also have the opportunity to engage in the most important intimacy-building skill in the world: listening. W.H.Auden wrote, “Among those whom I like or admire, I can find no common denominator, but among those whom I love, I can: all of them make me laugh.” More often than you can imagine, when people are stressed, worried, preoccupied, lonely or afraid, they carry this sign just beneath the surface: “Joy needed—please lighten up.” People who don’t take themselves too seriously give a great gift to those around them. In contrast, joy-challenged people face a serious handicap in trying to live in community. One of the hardest things in the world is to be right and not hurt anybody with it. Remember some time in school when you sat next to the smartest kid in class. Did you enjoy it? Being right (or more precisely, having the need to be right) is a terrible burden. In contrast, if you are willing to lighten up, even your mistakes can become bridges. Every single interaction we have with another person involves not simply exchanging information or performing tasks but also influencing each other’s moods and attitudes. What Daniel Goleman calls an “emotional economy” is “the sum total of exchanges of feeling among us". Emotions are more contagious than flu. Every time two people make contact, they come away feeling either better and more energized or worse and more depleted. It is as if we carry our own little emotional ATMs around with us all the time, and at each encounter we are either making deposits or withdrawals on the vitality of those around us. Some people contribute to the emotional economy; others are a drain. When some people call a meeting, you look forward to going. When someone else calls a meeting, you look for an excuse to leave early. People often use what researchers call “spatial orientation” to assess the state of a relationship. Our upper body unwittingly squares up, addresses, and “aims” at those who we like feel close to. We will tend to lean toward them. However, someone who is uncomfortable in a conversation will begin to angle their body away from the other person. The tendency to express relational dynamics by “angular distance” is so strong that it is often possible to identify the most powerful or high-status person seated at a conference table by the relative number of torsos aimed in her or his direction. Sometimes you can see a parent haranguing a child on some issue or the other. It is very clear that emotionally, for whatever reason, the child is overwhelmed or completely tuned out; he’s looking the other way, his head is hanging down, he’s responding with monosyllable or not at all. This conversation is not serving any productive purpose; it’s just an exercise in catharsis for the parent. Parents with high relational intelligence will say in these moments, “I’ve got to find another road.” Maybe that means we should have this conversation another time. Maybe that means we will have to find another way to discuss the matter. Maybe we will need to use fewer words and more questions. We may be able to push and manipulate somebody’s behavior but not their heart. Technology [has] transformed our lives. It always does and always will. The problem is that until it happens there is no way of knowing how it will change them. It often takes thirty years before the full implications of a new bit of technology reaches us. What AI will certainly do is change the way we work and live, with more and more parts of our lives organised for us by algorithms of one sort or another, from our refrigerators ordering our food on their own to our wristwatches monitoring our health and renewing our prescriptions. I worry about those algorithms. Algorithms may turn out to be the unnoticed controllers of our lives. AI will need IAs Forecasters predict that human skills will be confined to the Three Cs – the Creatives, the Carers and the Custodians. The Creatives will have the most fun and the most money, if they are successful; the Carers will be the most numerous because they include not only those who look after those in need, but also those who attend to our wants – in shops, schools, prisons, hospitals and any organisation you can think of. Then there are those who try to hold things together whom I call the Custodians. They include the executive part of the government, especially the civil service, but managers in every organisation will still be needed to plan and decide who or what does what and when. Even those driverless cars will still need to be instructed where to go. There will still be a lot of jobs, even more than before, maybe, but they will be different. My guess is that you can’t have AI without a lot of IAs (individual assistants). Short business life In my day most work was delivered by institutions, hospitals, schools, coal mines, steelworks, businesses of all sorts, small and big, the civil service, the armed services. I joined one of those businesses, an international oil company, Shell. They expected me to work with them until I was sixty-two, and on my arrival drew up a chart of the sort of career I was likely to have, with a range of increasingly senior jobs in a variety of countries. It looked exciting. Many years later I realised that not only did some of those Shell companies on the plan no longer exist, neither did the countries, at least not under the name they bore at that time. So quickly does the world change. Indeed, the average life of a business these days is only sixteen years. So how could they even think of offering you a job for life? What it means is that there is no longer such a thing as a secure job. There is no longer anyone looking after your future career as there was in Shell, planning your next move, the training you might need, even your medical requirements. You are on your own. Even if you are employed you will have to apply for any new positions that become available. Furthermore, once you are over fifty you will find those jobs increasingly hard to get. Portfolio and shamrock That is why I started to suggest that what I called a portfolio life would be the best alternative for people in that age bracket. By a portfolio life I meant a collection of small jobs, some paid, some unpaid but useful. Increasingly, however, a portfolio life began to be the life of choice for younger people, such as you. Sometimes it was because they did not fancy the controlled atmosphere of the large organisation and decided to try their luck outside. Mostly they valued the independence of the portfolio existence, risky though it was financially. Long ago, in one of my books, I suggested that organisations would increasingly resemble a shamrock with its three leaves making up the whole. One leaf would be the core employees, the second the sub-contractors and the third the individual experts or occasional workers whom it would be costly and unnecessary to employ full-time. More and more work, I suggested, would go to the second and third leaves because they would be cheaper, would not have to be on the organisation’s books or in their pension schemes. Increasingly that is what has happened. Of one thing I am certain: life for you, all being well, will be so long that one day you too will have to go solo, or portfolio, if you are going to continue to work, as I hope you will. More people than ever are working for money, as they always have, but in very different ways. No doubt those ways will change even more during your life, with automation doing a lot of the drudgery, but I feel sure that our human need to be productive will endure. Work will still be central to all our lives. A shamrock is a young sprig, used as a symbol of Ireland. The name shamrock comes from the Irish word seamair óg and means "young clover". All text in this post is from the First Letter in the book 21 Letters on Life and Its Challenges written by Charles Handy. Copyright © Charles Handy 2019. Published by Hutchinson, a part of Penguin Random House. Charles Handy has written this book for his four grandchildren. In the Introduction to the book, he writes:

"You are living in a very different world to the one I knew, but I suspect that the issues you come up against will not be that dissimilar. It is hard to learn from other people’s experiences, but my reflections may make you at least pause and think before you act, or, sometimes, think again after you have acted. These letters, you might say, contain all the stuff that I wished I had known when I was your age, before I went out into the world and had to make my own future, my own contract with life.” Charles Handy CBE (born 1932) is an independent Irish writer, broadcaster, teacher and philosopher specialising in organisational behaviour and management. He has been an oil executive, an economist, a professor at the London Business School, the Warden of St. George’s House in Windsor Castle and the chairman of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. He has been rated among the Thinkers 50, a private list of the most influential living management thinkers. Instead of doing what is ethical, we figure out what we want to do and then come up with the rationalization for doing it. Getting outside help when you’re emotionally involved in an issue is a key element to living a more ethical life. By correcting even “minor” ethical lapses, we get constant practice at living more ethically. How lucky we are that life is constantly presenting us with opportunities to build up our ethical muscles. Because ethical norms evolve, becoming an ethical person is a process or practice. Being open to seeing and correcting one’s current failings is essential to that process. Technology has made it essential to accelerate the evolution of our ethical behaviour. Science and engineering have given us physical powers that traditionally were thought of as belonging only to the gods. Only God could destroy cities with thunderbolts. Today, we can do the same with nuclear weapons. Only God could cause a flood that would necessitate Noah building an ark, whereas human-induced global warming threatens similar devastation. Only God could create new life forms, whereas genetic engineering allows us to do so routinely. Nuclear weapons, environmental crises, and genetic engineering are symptoms of a deeper, underlying problem: the chasm between our technological power on the one hand and our ethical development on the other. Humanity is like a sixteen-year-old with a new driver’s license who somehow got his hands on a 500-horsepower Ferrari. We will either accelerate our ethical evolution or we will kill ourselves. While we have made significant progress in all dimensions related to the survival of civilization, we still have far to go. No one person can solve this problem. But if enough of us move things a little, together we can change the substrate of the world and create new possibilities. That’s how slavery ended, women got the vote, and more. If enough of us work at accelerating humanity's ethical evolution, together we will not only triumph over the threats we face; we will also build a more peaceful, sustainable world that we can be proud to pass on to future generations.

Credits:

https://tinyurl.com/martinlindau https://tinyurl.com/yx9goj7q https://tinyurl.com/scaredemoji Porcupines don’t always want to be alone. But love turns out to be a risky business when you’re a porcupine. This is the Porcupine’s Dilemma: How do you get close without getting hurt? This is our dilemma too. Every one of us carries our own little arsenal. Our barbs have names like rejection, condemnation, resentment, arrogance, selfishness, envy, contempt. Some people hide them better than others, but get close enough and you will find out they’re there. We, too, find ourselves hurting (and being hurt by) those we long to be closest to. And, of course, we can usually think of a number of particularly prickly porcupines in our lives. But the problem is not just them. I’m somebody’s porcupine. So are you. In an image too wonderful to be made up, naturalist David Costello writes, “Males and females may remain together for some days before mating. They may touch paws and even walk on their hind feet in the so-called ‘dance of the porcupines.’" It turns out there really is an answer to the ancient question, how do porcupines make love? They pull in their quills and learn to dance. It’s time to pull in your quills and start dancing. Extracted from the book Everybody’s Normal Till You Get to Know Them by John Ortberg. Copyright © 2003 by John Ortberg. Publisher: Zondervan. Image credit: https://tinyurl.com/y5vm57xv

|

Vijayakumar Kotteri

Abstracts from works of different authors. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed