|

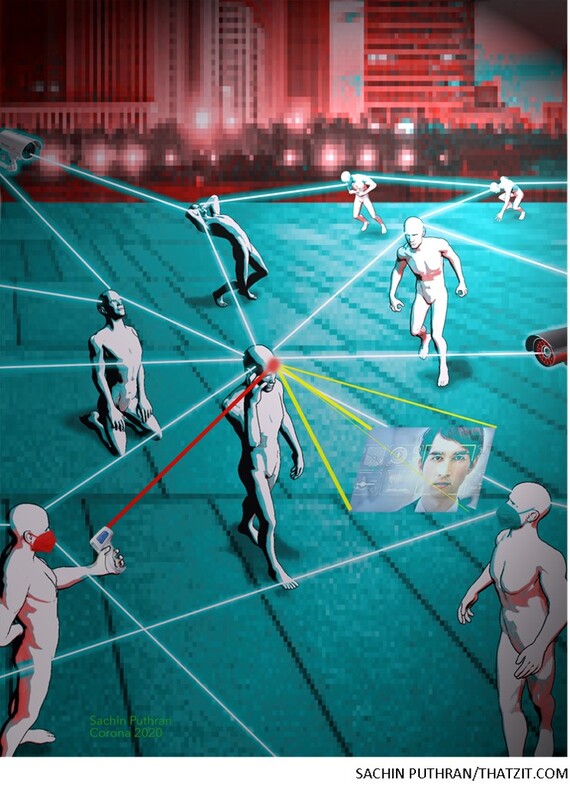

Humankind is now facing a global crisis. Perhaps the biggest crisis of our generation. The decisions people and governments take in the next few weeks will probably shape the world for years to come. We must act quickly and decisively. When choosing between alternatives, we should ask ourselves not only how to overcome the immediate threat, but also what kind of world we will inhabit once the storm passes. Many short-term emergency measures will become a fixture of life. That is the nature of emergencies. They fast-forward historical processes. Decisions that in normal times could take years of deliberation are passed in a matter of hours. Immature and even dangerous technologies are pressed into service, because the risks of doing nothing are bigger. Entire countries serve as guinea-pigs in large-scale social experiments. What happens when everybody works from home and communicates only at a distance? What happens when entire schools and universities go online? In normal times, governments, businesses and educational boards would never agree to conduct such experiments. But these aren’t normal times. In this time of crisis, we face two particularly important choices. The first is between totalitarian surveillance and citizen empowerment. The second is between nationalist isolation and global solidarity. Under-the-skin surveillanceIn order to stop the epidemic, entire populations need to comply with certain guidelines. There are two main ways of achieving this. One method is for the government to monitor people, and punish those who break the rules. Today, for the first time in human history, technology makes it possible to monitor everyone all the time. In their battle against the coronavirus epidemic several governments have already deployed the new surveillance tools. The most notable case is China. By closely monitoring people’s smartphones, making use of hundreds of millions of face-recognising cameras, and obliging people to check and report their body temperature and medical condition, the Chinese authorities can not only quickly identify suspected coronavirus carriers, but also track their movements and identify anyone they came into contact with. A range of mobile apps warn citizens about their proximity to infected patients. You might argue that there is nothing new about all this. In recent years both governments and corporations have been using ever more sophisticated technologies to track, monitor and manipulate people. Yet if we are not careful, the epidemic might nevertheless mark an important watershed in the history of surveillance. Not only because it might normalize the deployment of mass surveillance tools in countries that have so far rejected them, but even more so because it signifies a dramatic transition from “over the skin” to “under the skin” surveillance. Hitherto, when your finger touched the screen of your smartphone and clicked on a link, the government wanted to know what exactly your finger was clicking on. But with coronavirus, the focus of interest shifts. Now the government wants to know the temperature of your finger and the blood-pressure under its skin. The emergency puddingSurveillance technology is developing at breakneck speed, and what seemed science-fiction 10 years ago is today old news. If corporations and governments start harvesting our biometric data en masse, they can get to know us far better than we know ourselves, and they can then not just predict our feelings but also manipulate our feelings and sell us anything they want — be it a product or a politician. Even when infections from coronavirus are down to zero, some data-hungry governments could argue they needed to keep the biometric surveillance systems in place because they fear a second wave of coronavirus, or because there is a new Ebola strain evolving in central Africa, or because . . . you get the idea. A big battle has been raging in recent years over our privacy. The coronavirus crisis could be the battle’s tipping point. For when people are given a choice between privacy and health, they will usually choose health. The soap policeCentralised monitoring and harsh punishments aren’t the only way to make people comply with beneficial guidelines. Consider, for example, washing your hands with soap. This has been one of the greatest advances ever in human hygiene. This simple action saves millions of lives every year. While we take it for granted, it was only in the 19th century that scientists discovered the importance of washing hands with soap. Previously, even doctors and nurses proceeded from one surgical operation to the next without washing their hands. Today billions of people daily wash their hands, not because they are afraid of the soap police, but rather because they understand the facts. But to achieve such a level of compliance and co-operation, you need trust. People need to trust science, to trust public authorities, and to trust the media. Over the past few years, irresponsible politicians have deliberately undermined trust in science, in public authorities and in the media. Now these same irresponsible politicians might be tempted to take the high road to authoritarianism, arguing that you just cannot trust the public to do the right thing. Instead of building a surveillance regime, it is not too late to rebuild people’s trust in science, in public authorities and in the media. We should definitely make use of new technologies too, but these technologies should empower citizens. The coronavirus epidemic is thus a major test of citizenship. In the days ahead, each one of us should choose to trust scientific data and healthcare experts over unfounded conspiracy theories and self-serving politicians. If we fail to make the right choice, we might find ourselves signing away our most precious freedoms, thinking that this is the only way to safeguard our health. We need a global planThe second important choice we confront is between nationalist isolation and global solidarity. Both the epidemic itself and the resulting economic crisis are global problems. They can be solved effectively only by global co-operation. First and foremost, in order to defeat the virus we need to share information globally. That’s the big advantage of humans over viruses. A coronavirus in China and a coronavirus in the US cannot swap tips about how to infect humans. But China can teach the US many valuable lessons about coronavirus and how to deal with it. What an Italian doctor discovers in Milan in the early morning might well save lives in Tehran by evening. When the UK government hesitates between several policies, it can get advice from the Koreans who have already faced a similar dilemma a month ago. But for this to happen, we need a spirit of global co-operation and trust. Countries should be willing to share information openly and humbly seek advice, and should be able to trust the data and the insights they receive. We also need a global effort to produce and distribute medical equipment, most notably testing kits and respiratory machines. Instead of every country trying to do it locally and hoarding whatever equipment it can get, a co-ordinated global effort could greatly accelerate production and make sure life-saving equipment is distributed more fairly. Just as countries nationalise key industries during a war, the human war against coronavirus may require us to “humanise” the crucial production lines. A rich country with few coronavirus cases should be willing to send precious equipment to a poorer country with many cases, trusting that if and when it subsequently needs help, other countries will come to its assistance. We might consider a similar global effort to pool medical personnel. Countries currently less affected could send medical staff to the worst-hit regions of the world, both in order to help them in their hour of need, and in order to gain valuable experience. If later on the focus of the epidemic shifts, help could start flowing in the opposite direction. Global co-operation is vitally needed on the economic front too. Given the global nature of the economy and of supply chains, if each government does its own thing in complete disregard of the others, the result will be chaos and a deepening crisis. We need a global plan of action, and we need it fast. Another requirement is reaching a global agreement on travel. Suspending all international travel for months will cause tremendous hardships, and hamper the war against coronavirus. Countries need to co-operate in order to allow at least a trickle of essential travellers to continue crossing borders: scientists, doctors, journalists, politicians, businesspeople. This can be done by reaching a global agreement on the pre-screening of travellers by their home country. Unfortunately, at present countries hardly do any of these things. A collective paralysis has gripped the international community. There seem to be no adults in the room. Humanity needs to make a choice. Will we travel down the route of disunity, or will we adopt the path of global solidarity? If we choose disunity, this will not only prolong the crisis, but will probably result in even worse catastrophes in the future. If we choose global solidarity, it will be a victory not only against the coronavirus, but against all future epidemics and crises that might assail humankind in the 21st century. Copyright © Yuval Noah Harari 2020

Adapted from the original written by Yuval Noah Harari. Read the complete article here. Yuval Noah Harari is historian, philosopher and the author of Sapiens, Homo Deus and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Sachin Puthran is an artist-entrepreneur, as creative as he is with pencil and paper as he is adept at wielding the latest technology to cater to varied communication needs.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Vijayakumar Kotteri

Abstracts from works of different authors. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed